Closing the gap on the torture trade

by Joëlle A. Trampert

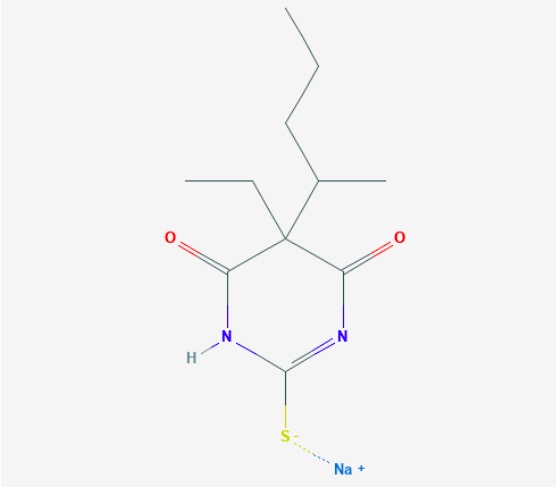

2D Structure of Sodium thiopental, a pharmaceutical chemical employed in lethal injection execution. Source: Pubchem, National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/23665410)

The prohibition of torture is codified in Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the regional human rights treaties. It has also been accepted as an international human rights norm of ius cogens. The Convention Against Torture (‘CAT’) obliges the 171 States party to the treaty to prevent and punish torture, and refrain from expelling, refouling or extraditing a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he or she would be in danger of being subjected to torture. But as Ambassador Skoog, Head of the European Union Delegation to the United Nations, remarked in his introductory speech for the Alliance for Torture-Free Trade online event last December, ‘there is no rule at the international level to regulate the trade in goods used for torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. (…).’ For EU member States, binding rules to this effect have been in force since 2006, and Regulation (EU) 2019/125 of 16 January 2019 is currently the most important regional legal regime prohibiting and controlling trade in goods which could be used for capital punishment, torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (‘CIDTP’). Where this Regulation does not apply, States can lawfully allow the manufacture and transfer of goods used for torture or other CIDTP, as well as related services such as technical assistance and training. Amnesty International and Omega Research Foundation have also found that States ‘regularly permit or facilitate arms and security equipment trade fairs and other related exhibitions where law enforcement equipment that could be misused for torture and other ill-treatment is promoted.’ Despite the absolute and non-derogable nature of the prohibition of torture, and despite the obligation to prevent and punish torture, there is little stopping States, companies and individuals not only from directly contributing to torture, but also from promoting or even profiting from it. However, change is underway. Against the backdrop of the broader business and human rights debate, there is a momentum at both the regional and international level to close this gap. On 31 March 2021, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe adopted Recommendation CM/Rec(2021)2 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on measures against the trade in goods used for the death penalty, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. This blog post briefly highlights the Council of Europe initiative and positions it around the broader problem of State facilitation of torture.

The Council of Europe’s Recommendation on Torture-Free Trade

In 2018, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted Recommendation 2123 (2018) entitled ‘Strengthening international regulations against trade in goods used for torture and the death penalty’. The Parliamentary Assembly considered that on the basis of existing legal obligations, ‘Council of Europe member States are required to take effective measures to prevent activity within their jurisdictions that might contribute to or facilitate capital punishment, torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment in other countries, including by effectively regulating the trade in goods that may be used for such purposes.’ [§3] In other words, the Parliamentary Assembly suggests that in addition to prohibiting torture and refoulement and imposing positive and procedural duties on States within their territory, Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (‘ECHR’) requires States to take measures to prevent conduct which facilitates torture extraterritorially. Although extraterritorial human rights obligations remain contentious, the Parliamentary Assembly’s idea is not new; it closely reflects a paragraph in the Committee of Ministers’ Recommendation to member States on business and human rights, adopted in 2016: ‘[i]n order not to facilitate the administration of capital punishment or torture in third countries by providing goods which could be used to carry out such acts, member States should ensure that business enterprises domiciled within their jurisdiction do not trade in goods which have no practical use other than for the purpose of capital punishment, torture, or [CIDTP].’ [§24]

Following the draft Recommendation prepared by the Steering Committee for Human Rights, the Committee of Ministers adopted the Recommendation on measures against the trade in goods used for the death penalty, torture and other CIDTP at the 1400th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies (‘the Recommendation’). First, the Recommendation calls on member States to ‘regularly review their national legislation and practice related to the trade in goods that are inherently abusive, as well as in goods which can be misused for the death penalty, torture and other [CIDTP]’. Second, it recommends member States to ‘ensure (…) a wide dissemination of the principles set out in the appendix to this Recommendation among competent authorities, notably those implementing and overseeing regulation of the trade in goods that can be used for the death penalty, torture and other [CIDTP], specifically including (…) civil society organisations’, thereby underlining the importance of the work of NGOs such as Amnesty and Omega. The Steering Committee for Human Rights has also made clear that the Recommendation aims to send a strong signal to other international bodies, namely the UN. This is reflected in the preamble of the Recommendation, which explicitly refers to UN General Assembly Resolution A/RES/74/143 ‘Torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’; General Assembly Resolution A/RES/73/304 ‘Towards torture-free trade: examining the feasibility, scope and parameters for possible common international standards’; and the subsequent report of the United Nations Secretary-General A/74/969.

Trade as a Form of Facilitation

Already in 2004, UN Special Rapporteur Theo van Boven concluded in his report that the obligation to prevent torture ‘necessarily includes the enactment of measures to stop the trade in instruments that can easily be used to inflict torture and ill-treatment’. As explained above, the Parliamentary Assembly also found that Article 3 ECHR requires States to take such measures in their 2018 Recommendation. This departs from the traditional approach in international human rights law, which only assigns obligations to States vis-à-vis individuals within their jurisdiction. Under the Court’s current jurisprudence, the argument that an obligation is owed to an individual who has never set foot on that State’s soil, or is not within an area under effective control of that State or under State agent authority and control, is more tenuous. Over the recent years however, there have been noteworthy developments on the interpretation of the notion of jurisdiction in international human rights law. Moreover, the UN International Law Commission (‘ILC’) said in its Commentary to Article 16 of the Articles on State Responsibility: ‘a State cannot do by another what it cannot do by itself. (…) [A] State may incur responsibility if it (…) provides material aid to a State that uses the aid to commit human rights violations.’ [§6 and §9] The export of goods which are meant to be used or can be used for the purpose of torture can arguably be classified as the ‘material aid’ mentioned by the ILC. My PhD explores whether in fact the prohibition of torture necessarily includes not only the prohibition of extradition and export, but also the prohibition of many other forms of assistance, provided certain conditions are met. I argue that the obligation to restrict the trade of torture equipment is yet another example of a rule prohibiting State facilitation of torture, not too dissimilar to the obligation of non-refoulement. Stopping the torture trade is a worthy goal in and of itself, but the quest to prevent and supress torture does not end there; States can assist torture and capital punishment in a myriad of ways, e.g. by providing airports and airspace or mutual legal assistance. Even though such a ‘principle of non-facilitation’ is not explicitly mentioned in the text of the Convention, there is no reason the Court could not interpret Article 3 this way, as the Parliamentary Assembly suggested in their 2018 Recommendation. The Committee of Ministers’ Recommendation allows room for this too. One of the recitals considers ‘the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights…’. The jurisprudence of the Court is constantly developing, expanding and fine tuning the scope of the obligations imposed on Council of Europe member States. As is well known, the principle of non-refoulement, explicitly enshrined in Article 3 CAT but not in the ECHR, was first considered by the Court in Soering v UK in 1989. In Soering, the Court held for the first time that the decision to extradite the applicant would, if implemented, give rise to a breach of Article 3 ECHR, due to exposure to the so-called ‘death row phenomenon’. It was not until Al-Saadoon and Mufdhi v UK in 2010, that the Court concluded that the death penalty not only amounted to inhuman or degrading treatment in violation of Article 3 ECHR irrespective of the circumstances, but also, due to evolving State practice, violated the right to life (cf Öcalan v Turkey and Bader and Kanbor v Sweden), thereby broadening the scope of the principle of non-refoulement to Article 2 ECHR (see also Al Nashiri v Poland). The Court has also included the principle of non-refoulement for Article 6 ECHR (see Soering and Al-Saadoon) and Article 5 ECHR (see Othman (Abu Qatada) v the United Kingdom and El-Masri v the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). Lastly, the threshold for treatment that constitutes ‘torture’ or ‘inhuman and degrading treatment’ has also evolved (see Selmouni v France). These developments show how the Convention, a ‘living instrument’, is adaptable to present-day conditions and societal needs.

In conclusion

International trade is an important field to tackle, and tighter and more principled prohibitions and restrictions will have a great societal impact. Besides the importance of preventing conduct which contributes to or facilitates torture for the sake of the integrity of the norm, namely the prohibition of torture, the focus on trade has an important normative dimension too: States must not benefit from, or allow companies or individuals to profit from, the trade in goods which are used to commit torture or other CIDTP. In the further implementation of the absolute prohibition of torture, torture-free trade is a good place to start – but it is certainly not the place to stop.

Bio:

Joëlle Trampert is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. Her PhD research is on State responsibility for facilitating serious violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law, as part of the Vici-funded ‘Rethinking SLIC*’ project.