Decent work for Migrant Domestic Workers: An Unrealised Promise?

By Natalie Alkiviadou

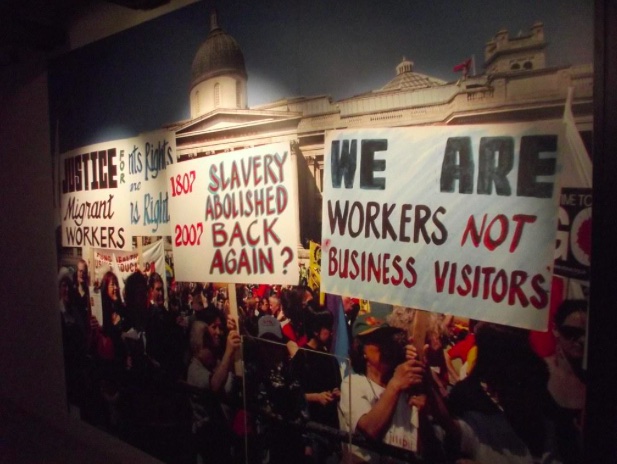

"International Slavery Museum - Albert Dock - Liverpool - Legacies of slavery - Migrant domestic workers and Kalayaan at the May Day Rally 2007" by ell brown

Introduction

In 2019, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated that there were approximately 11.5 million migrant domestic workers (MDWs) around the globe, 8.5 million of whom are women. The entrance of women into the labour market and ageing populations have been central factors contributing to the rise in the demand of cheap female migrant domestic workers (FMDWs). FMDWs fill the gaps in ineffective systems of social welfare, which cannot support, inter alia, an ageing population. In this ambit, FMDWs are caught at the ‘the intersection of care work exploitation with gender, ethnic and migrant oppression in the context of a globalising world.’ This piece is based on research conducted on the situation of FMDWs in Cyprus and seeks to set out the international legal framework that exists to protect this group of workers.

MDWs continue to constitute one of the most invisible and vulnerable group of workers. For example, research into the United Kingdom, France and Ireland suggests that the ‘precarious immigration status of many migrant domestic workers’ renders the enjoyment of employment rights ‘largely illusory in practice.’ As a result, MDWs often suffer from a ‘decent work deficit’ which is defined as “the absence of sufficient employment opportunities, inadequate social protection, the denial of rights at work and shortcomings in social dialogue.”

Challenges

The challenges faced by MDWs result from factors such as the invisibility of their work, their high dependence on employers (including vis-à-vis their residence status) and the fact that they reside, in most cases, within the house of their employer, with no clear distinction being made between their place of abode and rest on the one hand and work on the other. These factors are results of deeper structural reasons. Firstly, as argued by Anderson, immigration law ‘moulds migrant domestic workers…into precarious workers.’ Further, Kontos argues that the work of MDWs has been constructed in such a way that the MDW undergoes a process of familialization, namely, that she becomes part of the employer’s family whilst, at the same time, she is defamilialized from her own family due to the long-term separation attached to this line of work. The above situation renders MDWs ‘particularly susceptible to abuse and exploitation.’ Moreover, the low value associated with domestic work impacts the general structure that underlies the experiences of MDWs. More specifically, MDWs are tasked with household maintenance and caregiving, which have traditionally been undertaken by female members with no pay. As well as the general vulnerability attached to the status of MDWs, who are often ‘invisible’ in the home of their employers, the temporary nature of their stay leads to a variety of issues in relation to, for example, residency, health care, family life, freedom of association and democratic participation. Here, it is noteworthy that the European Migration Network’s definition of temporary migration is ‘migration for a specific motivation and/or purpose with the intention that, afterwards there will be a return to country of origin or onward movement.’ The above-described reality was reflected in research carried out within the framework of a project on the rights of FMDWs in Cyprus, funded by the Hellenic Observatory of the London School of Economics and Political Sciences. This research emanated from 150 questionnaires, 21 in-depth interviews and two focus groups of FMDWs working in Cyprus. It revealed a multitude of challenges such as long working hours, a heightened possibility of abuse, restrictions to private and family life and low, late or no pay.

National Laws: Examples

In France, domestic work is legally recognized as real work, with the relevant law being ‘one of the most detailed attempts to gear the employment contract specifically to the domestic work relationship and enforce it in such a way as to prevent abuse.’ However, its enforcement is far from perfect since the law necessitates a court order to allow for an inspection of a private home. This model is adopted in countries such as Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands, all of which have specific legislation on the employment of domestic workers. In Cyprus, however, there is no law that governs the entry, stay and employment of MDWs.

European Law: The European Union and the Council of Europe

In November 2000, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the regulation of domestic help in the informal sector. This resolution asked the European Commission to, amongst others, include domestic workers in existing and future employment directives, taking into account the specificities of their work situation, regulate a maximum number of working hours and ensure social security. Despite this resolution, there has been no influence on EU policy or Law.

On the other hand, however, the EU has passed the Directive on providing for minimal standards on sanctions and measures against employers of third country nationals staying illegally which proposes less severe penalties for employers of irregular domestic workers insofar as there are ‘no particularly exploitative working conditions.’ (Article 5.3) This demonstrates the enhanced acceptance or even implied acknowledgement that irregularity in residence comes into play within the sphere of domestic work. The use of the word ‘particularly’ before exploitative working conditions also begs the question of whether the EU is implicitly recognizing that minimal exploitative working conditions are to be tolerated when it comes to migrant domestic workers.

On the Council of Europe level, the approach is different to that of the EU. In 2001, Recommendation 1523 on Domestic Slavery was adopted, followed in 2004 by Recommendation 1663 on Domestic Slavery: Servitude, Au Pairs and ‘Mail-Order Brides.’ The two recommendations are placed within the framework of linking domestic work with the possibility of forced labour and trafficking. The 2004 recommendation calls for a charter on the rights of domestic workers to allow for, amongst others, the recognition of domestic work as real work, the right to health insurance, family life and a legally enforceable contract with adequate information on the working hours and rights. It is significant that, unlike the 2000 resolution of the European Parliament, the 2004 recommendation makes specific reference to the right to private and family life. This is of central importance if the familialization process, mentioned above, is to be circumvented by the construction of coherent and sustainable structures in which MDWs are granted access to the same rights (including labour rights) as other groups of workers.

International Law

The rights of domestic workers are slowly expanding within the framework of international human rights law, with developments such as the ILO Domestic Workers Convention 2011 which provides for, inter alia, the realization of human rights such as the freedom of association and the elimination of discrimination effective protection against abuse and minimum wage. This document demonstrates a ‘global struggle to improve the working conditions of a sector which has been historically excluded from the scope of labour law.’ The United Nations Committee for Migrant Workers has highlighted that their rights ‘should be dealt with within the larger framework of decent work for domestic workers.’

Conclusion

It is imperative to re-visit the international and European legal frameworks, vis-à-vis the rights of MDWs, and ensure that a process of gender mainstreaming is incorporated in any initiative given the disproportionate number of women who make up this workforce. It is imperative that States ratify the ILO Convention and make separate legislation tackling the challenges faced by this group of workers providing them with, inter alia, access to human rights, a minimum wage and thus a structured employment setting. Without such steps, the State is essentially ‘creating and perpetuating…the structural disadvantages faced by migrant domestic workers.’ To this end, it is rather unfortunate that the EU, whose directives are binding on Member States, has not yet taken steps in this direction, despite the resolution of its parliament in 2000 (notwithstanding the fact that it is lacking, for example, in relation to the right to family life). As noted by the ILO, unless steps are taken to improve national legislative frameworks, decent work for MDWs will remain an ‘unrealised promise.’

Bio:

Natalie Alkiviadou is a Senior Research Fellow at Justitia, Denmark.